NOW YOU SEE IT: The Owens Valley and Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra

Questions about the meaning of existence lie behind every landscape photograph. An unsparing answer (for it is a single answer) may not be to everyone's taste. But it is important, and necessary, to ask.

We could see a little into the distance now. Colour came into the eastern sky and almost immediately dawn crept over the land. Dawn light imparts a calmness to the air. So beautiful, so new. A sense of joy in the here and now and all that we value in our surroundings. A stone, a post, a building has greater depth and more solidity at this hour and these objects are consciously more individual. A post is more essentially a post: set off in a field it holds its own and differentiates itself from all other posts; and the ragged cottonwood in itself stands free of all other trees. Words and phrases, some classical, some biblical, some chemical here take on the meaning of reality. Ashes and dust. To dust. Dust covers the display cases in the Laws museum ('please shut the door; dust is a problem') and dust devils swirl across the road. The sun is fully up now. Unnamed natural beauty stretches to the Valley floor: the terrible immutability and continuity of landscape. Do you feel cheated of your heritage? Troubled in any way by a lack of cultural continuity in your life? Do you feel robbed of your soul by these monuments of natural indifference? Then you can take a running jump so far as these hills are concerned. They are, to paraphrase T S Eliot, what they always were.

It may be my peripatetic childhood but I have always been fascinated by the relationship between change and continuity. We like to assume that there is continuity in time as there is in space; that most of the objects we come across in the course of our lives will stay the same. As landscape photographers, we like to think that the appearances of these objects, the places in which they are set and the events that occur within these places will be instantly communicable to others. It is a rude awakening therefore that with the majority of the locations we encounter in North America, nothing dissolves with quite the speed of the quite recent past, by which I mean the past of the last mid-century. Small changes in themselves may not be of any great substance but their effect is to change everything in less than a lifetime. Little wonder then that the trend of Western American landscape photography is one of hyperrealism in flight from barely acknowledged sadness and loss.

But not here. It is the apparent lack of environmental, cultural and even climate change that is so remarkable about the Owens Valley.* Nor is there any of the strained, artificial feel of much modern experience when it can seem as if the landscape through which we move is just a digitised illusion. For to enter the Valley is like stepping into a world we have lost. Edward Weston came here and J B Priestley ('geology by day, astronomy by night'), and Ansel Adams who slept atop his jeep: all would still recognise an open stage on which to contemplate the relation of man to a beautiful but an unforgiving landscape. To this I would add that the Valley expresses unequivocal continuity in the human span of time. We know here what the present will look like when it becomes the past and that is remarkable enough to be worth photographing even if it were not as beautiful as it is.

Settlements in the Owens Valley are not historical re-creations. There is an unpremeditatedness about Keeler at the Valley's southern end that is the opposite of facadism. Ordinary things count for much more in Keeler than things intended to make an impression. And neither is Keeler a ghost town. Real people live here albeit with a slight air of furtive hostility. With a modern-day take on Grapes of Wrath, Keeler's inhabitants are now in flight from urbanisation and pollution as well as from erosion, having become expats in their own country. When you are faced with overpopulation, move to one side, get out of the way. It can sometimes feel as if decades in America are not in a simple, entirely straightforward line of descent. It's rather a shifting of the frame, a leaving behind. Better: it just moves to one side in recognition that there is a deeper relationship with landscape that goes beyond even memory and inherited culture.

Ansel Adams mentions the diminutive narrow-gauge railway built '300 miles too long or 300 years too soon' that until 1960 ran up the Owens Valley from its terminus in Keeler. J B Priestley who came here in the 1930s also refers to a little train 'which lights up the immense distances and loneliness of that country.' Ansel's little railway is long abandoned but persists in the memory as a kind of Surrealist painting, at once realistic and incorporeal, a natural inhabitant of the desert plain but kin to the crawling ant and the melted watch.

To really 'get' the Owens Valley, we need to see that this theme-park-sized but entirely genuine railway was a symbol for something very much bigger than itself. Railroads all but created Far Western latitude and longitude. They enabled the commerce and the communication that held the country together through the middle decades of the last century. Before 1960 and the construction of the interstate highway system, it was not so much road and car but rail that was the inextricable part of American culture.** But with the railroad's displacement from the centre the tenor of life changed and with it the tenor of landscape photography. From a dynamic epic of cultural fluidity, photography became a muted story of suburban and light-industrial prefabrication (mainly unpeopled) as intensely and very successfully captured by the photographers of the 'new topographics.'

This explains why the importance of the railroad in American art (and we should certainly include art photography) is underappreciated today. At key points in the narrative the railroad had permeated cinema, the rhythms of popular and orchestral music (e.g. the opening glissando of Rhapsody in Blue), the visual arts (viz Edward Hopper), literature (Thomas Wolfe, Scott Fitzgerald --whose narrator in Gatsby surveys recent events in his life from a train window whilst 'rolling westward into the republic in the night'), and in particular photography (Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Weston, John Vachon, Walker Evans, Jack Delano and Winston Link --to name but a few). It would be easy, of course, to overstate this influence. Novels, short-stories, music and paintings all have themes that have nothing to do with transportation and the railroad is only a part of the cultural backdrop of these works. But consider this: if in the 1940s and 1950s you wanted to take stock of your life; if you wished to embark on a new experience whilst simultaneously reassessing your past: then you would likely have done so on a train.

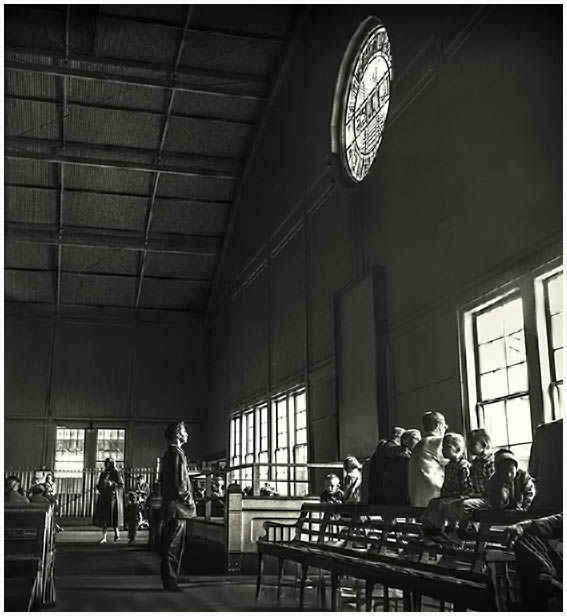

More than that, a sense of the inevitability of departure can be felt in the gestures and in the expressions of people going about their day-to-day lives. Repose in a public American scene through the 1950s is seldom a stasis; more often it is a pause in transit, and this is something that you do not generally find in European street photography. (Being relentlessly on the move is often misconstrued in Europe as an American sense of 'optimism.') There is therefore some real metaphorical truth in the idea that mid-century America was a vast station waiting-room with generations of passengers poised momentarily between birth and death.

A portrait of Lisette Model by Imogen Cunningham illustrates perfectly this photographically-arrested motion. Lisette emigrated from Austria and France to the United States in the late 1930s where she photographed the famous 'Running Legs' series in New York --whereupon Ansel Adams asked her to come and teach photography in San Francisco. When Lisette arrived there in 1945, she was photographed by Imogen Cunningham pausing in front of a shop window with her trademark Leica round her neck. (This was an intentional echo of the remarkable window-images Lisette had already made on Fifth Avenue.) There is a sense of expectation about this scene that will never be completely static even before you realise that its subject had spent four and a half days on a transcontinental rail journey to get to that position in time and space.

Even better, we might consider Bartok's cosmopolitan, multi-layered musical reverie the Concerto for Orchestra, which I personally believe was initially conceived (though commissioned and completed later) whilst on another transcontinental rail journey from New York to the West Coast in 1940, its thematic meditations on the meaning of life, the coming of war and the homesickness of exile inspired by the immensity of landscape sweeping past the composer's window. (Bartok had undertaken other transcontinental rail journeys in 1927-28 whilst performing in a number of American cities.) Bartok instinctively apprehended landscape in musical thought and was known to have kept careful notes of his experiences in his own musical code. In the Concerto for Orchestra there is undeniable pathos, longing and regret: but there is a difference between pathos and aura. 'Aura,' said the philosopher Walter Benjamin, 'is the unique phenomenon of distance' and it is aura and not pathos that is the dominant characteristic of the Concerto. Indeed the aura of landscape gives impetus to the episodic nature of Bartok's Concerto and binds its movements firmly together. Bartok never felt entirely at home in America but I believe that he wrote the truest evocation of the Western American landscape in any medium.

We could say with justice then that he view from any train window on the North American continent was a kind of thinking motion, a place to reflect on the rapidity with which existing things sweep past and are carried away:

By inducing a kind of hypnotic state, the rhythmic sounds of those mid-century rails accessed the unconscious mind in a manner foreign to travel on an open road. Quadrupedante putrem sonitu quatit ungula campum. 'Hooves, with their four-footed galloping sound, are shaking the powdery plain.' Campum ungula, ungula campum, campum ungula...the narrow, fragile, wooden wagons of the Owens Valley still drum across their dusty landscape, disappearing before our eyes into the vastness of the American West, the irrepressible hooves of Time.

*The extraction of water from the Owens River in the 1920s and 1930s did result in some 'desertification' that may not have been present in the past, or not to the same degree.

**Jet-powered transcontinental air travel also began in 1960.

Bad Water, 2007 Archival pigment print

Tucki Mountains, 2007 Archival pigment print

Keeler 2007 Archival pigment print

Keeler 1991 Gelatin silver print

Owenyo 1959 Gelatin silver print

The Western Gate 1958 Archival pigment print

Near Candlestick Point 1957 Gelatin silver print

All text and images Copyright R E Field

For more of my Owens Valley images please see the Far West gallery on this site.